- It’s What We Do

- Riding the Cordillera Blanca – South America at its best

- BMW F800GS – Off to the Safari Enduro

- Industry Player – Geeze Goldhawk

- White sand to red dust – A PLB story

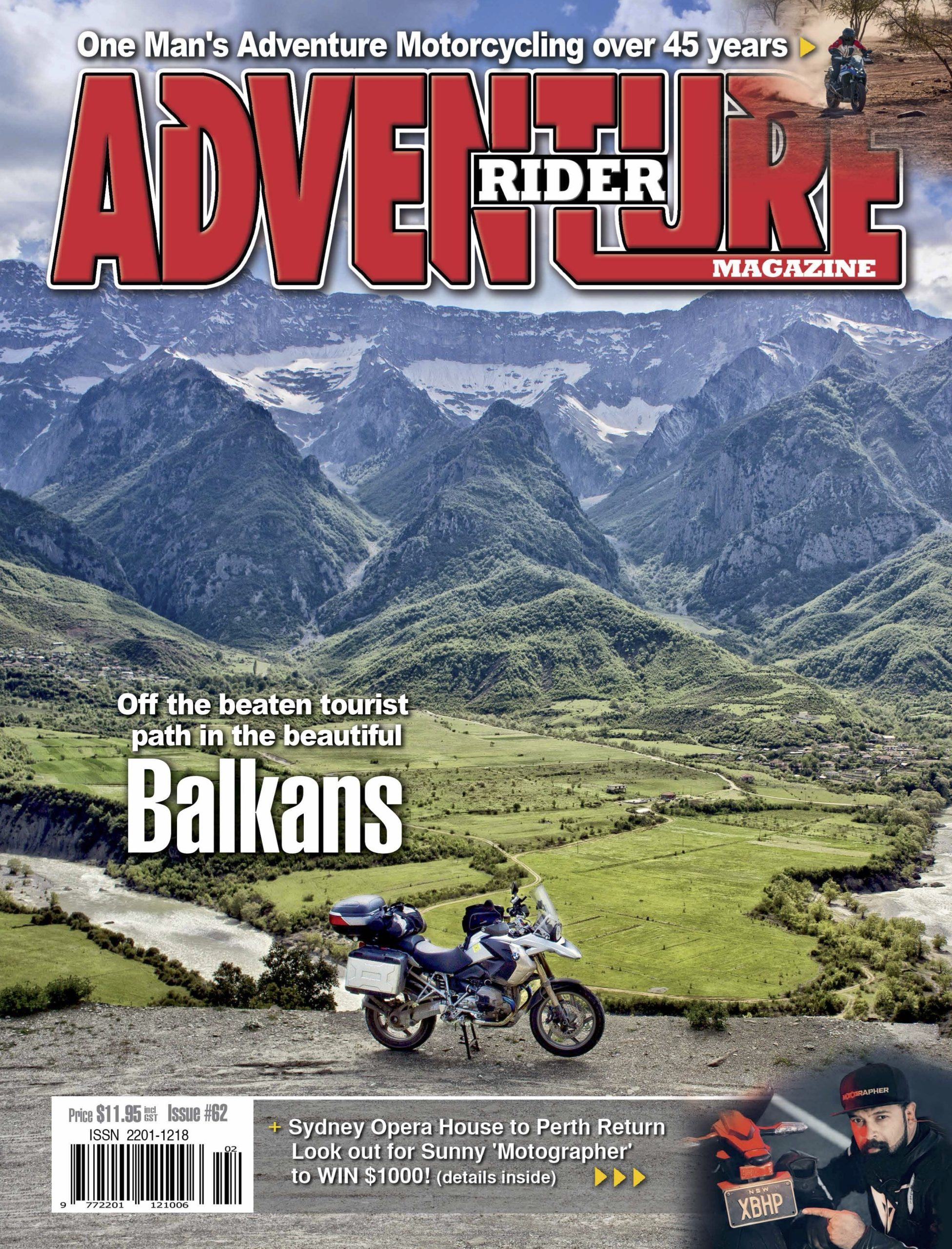

- Crazy Kunzum La – A tough run in the Himalayas

- Ladies only – BMW Off Road Training

- Off-road Test – Husqvarna 701 Enduro

- Across Australia – From the Indian to the Pacific

- Tour Of Duty: A Victorian three-day

- KTM Rallye 2016 – KTMs all over the place

- Domestic bliss – At home with the Ducati Multistrada Enduro

- Reader’s Ride – The Flinders

- Trials and tribulations with Karen Ramsay

- Dunns swamp – Another great secret location

- How To Ride with Miles Davis

- Checkout

- Fit Out

Riding one of the world’s most basic motorcycles through one of the world’s harshest environments proved no problem for Chris Shaw. He tells of just a single day out of a life-changing journey.

At sea level there’s an effective oxygen content of 20.9 per cent but at 4500m it’s almost halved. Any kind of exertion results in a sensation not unlike drowning on dry land.

At sea level there’s an effective oxygen content of 20.9 per cent but at 4500m it’s almost halved. Any kind of exertion results in a sensation not unlike drowning on dry land.

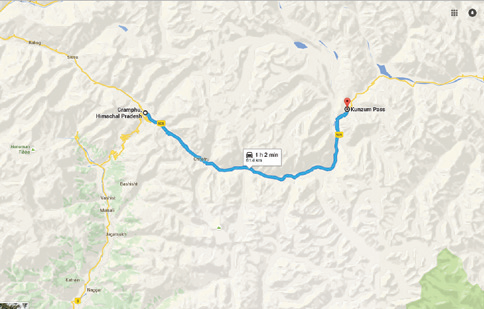

Kunzum La (Kunzum Pass) is in India’s eastern Himalayas at an elevation of 4590m. Considered the ‘Gateway to Spiti’, it’s the only motorable route connecting Kullu and Lahaul to the Spiti Valley. Often impassable due to avalanches or heavy snows, the rough and narrow road hugs the banks of the fast-flowing Chenab River, providing breathtaking views of the Chandra-Bhaga mountain range and the second-longest glacier in the world, Bara-Shigri.

We had to cross it.

Hurry up and wait

We were awake at 5:10am, groggy and confused by the sound of water rushing through the shallow channel beside the guesthouse. The notion that it might be a wall of mud and slush barrelling down the mountain to bury us alive in our beds and sweep the building away briefly panicked me, but a few seconds later (and not yet dead), I reinserted my earplugs, ignored the bright shards of sunlight stabbing at my eyes, tucked my feet into a warm fold of musty-smelling duvet, and went back to sleep for half an hour.

Snorting himself awake, my partner in crime, Tim, prodded me in the ribs with what I hoped was his finger. Quickly, before the biting mountain air could steal the bed-warmth from our skin, we shivered into crusty jeans and dusty riding jackets.

We should’ve just stayed in bed. We were riding with a group of Royal Enfield riders from New Delhi – ‘The Bike Blazers’ – led by Jay, whom we’d met on a previous trip, and although we’d all agreed to an early start the guesthouse kitchen staff were so slow to commence their culinary duties that, 90 minutes later, we were still waiting for our breakfast.

However, the day’s ride promised to be gruelling and our physical reserves would undoubtedly benefit from a good shot of caffeine, toast and omelette energy. So we sat. And we waited.

Done

The ride to Kunzum Top was spectacular and we were all glad to note the frightening drop-offs of previous days had

mellowed into ‘gradual rock-strewn slopes’ rather than ‘sudden plunging deaths’. The air was still, warm and aggrieved by no sound other than that of our Enfields, which were thumping contentedly. They were positively purring, actually. Beneath a cloudless blanket of turquoise blue, past rippling lines of prayer flags that snapped in the breeze, we rode on barren, drab-tan coloured hills that bellied up to saw-toothed, snow-capped Himalayan peaks. I was fed, rested and riding a delightfully charismatic motor-cycle in the Himalayas; there was quite literally nowhere else I’d have rather been.

Upon reaching the highest point on Kunzum Pass we circled the stupas – religious monuments – in a clockwise direction to request safe passage from whichever deity was watching, then parked the bikes, posed for pictures and took a few moments to contemplate our accomplishment. Kunzum had been the monster under the bed. It was both the thorn in the side of the trip and the key to its completion. If it’d proved impassable, reaching Manali would have been impossible and we would’ve been forced to turn around and ride back to Shimla. But after months of planning and five days of hard riding we’d made it.

Not for everyone

From Kunzum Top we rode 13km to Batal, a one-horse settlement whose horse was missing.

We were greeted by a weathered couple who graced us with steaming cups of chai and wide, welcoming smiles. For 40 years, in communal buildings constructed from river rock, stone and concrete, they’d pro-vided emergency lodging and basic meals for travellers caught out by the conditions or exhausted from the mental and physical strain of negotiating the treacherous roads.

All things considered, the accommodations were quite cozy. Interiors stained blue and yellow by sunlight filtering through coloured tarpaulin roofs were insulated from the most persistent of draughts by groundsheets draped over inner walls. Thick quilts of questionable cleanliness provided additional warmth. The scenery was staggeringly beautiful, but I couldn’t imagine living such a bleak and unforgiving existence. The long winters, lack of resources and weather-induced, pseudo-solitary confinement would quickly tarnish the allure of being in such a gorgeous location.

’S no joke

Just outside Batal we encountered our first snow obstacle. Two metres deep and 10 metres wide, it stopped us dead in our tracks. A front-end loader was busily working to uncover the road but there was no way we were getting through any time soon. The driver impatiently waved us away.

We would have to go around.

The first snow crossing was our detour, a broad plain sandwiched between the snow-covered road and the fast-flowing Chenbu River. We only needed to cover 100 metres or so of the gently inclined slope, but with street tyres treaded for water displacement rather than for aggressive grip on dirty grey snow and ice, it was more than far enough. Our individual attempts were met with varying degrees of success.

When the Indian lads lost traction they tended to deliver fistfuls of throttle that spun their rear tyres, digging their bikes into narrow, slippery trenches, whereas John, Tim and I understood that less throttle would give the rear tyre more chance to grip and drive.

Last up, Tim received an enthusiastic round of applause after crawling slowly, deliberately and unaided across the snow before delivering a burst of acceleration that propelled him through the ditch and onto the rock- and rubble-strewn road in a flail of elbows and outstretched flapping legs.

Getting’ high

It’s hard to adequately convey to someone who’s never done it just how hard it is to push a 180kg bike up snow- and slush-covered inclines in the thin air at 4500m altitude. Believe me when I tell you it sucks.

Shortness of breath, nausea, dizziness, sweating and fatigue might be symptoms of a heart attack, but they’re also signs of Acute Mountain Sickness. That can lead to pulmonary and cerebral oedema, both of which are potentially fatal. People suffer coronaries at every altitude but AMS isn’t considered a threat until 2500m. We were almost double that.

So wrong

Snow crossing number two featured walls of snow five metres deep that framed a slushy 80-metre long corridor bookended by frigid pools of melt. Traction was non-existent. Front wheels slid one way while back wheels spun and went the other. Fortunately, Rajesh’s recently acquired passenger, Rigzig, was there to save the day. Unfortunately (for him), he failed to take into account a key consideration when attempting to push a motorcycle in mucky conditions: positioning.

Standing directly behind a spinning rear wheel will invariably result in the pusher wearing whatever is bogging down the pushee. In this case, mud and slush. As Rigzig hunkered down and enthusiastically shoved, Rajesh fed in an even more enthusiastic dollop of throttle. A plume of icy mud and water spat backwards, coating Rigzig from head to toe. It felt wrong to laugh, but I did it anyway.

More of the same

The third snow crossing was la Grande Fromage of the day’s snow crossings. It was 300 punishing metres that could be neither avoided nor ignored.

A bulldozer was working to clear a path when we arrived, but as soon as there was room to slide by the heavy machinery I jumped the queue and made the first assault. No more than a couple of metres in the back tyre started spinning. Standing, leaning forward and pushing on the bars I attempted to walk the bike up the slope without losing my balance or running over my own feet. At that point it was all hands to the wheel as the guys rushed to help – pushing, pulling, slipping and falling in the slush they moved me forwards. At the top of the rise my heart sank at the sight of another, albeit slightly smaller, neighbouring slope, beyond which lay the beautiful traction and welcome stability of wet gravel.

No sooner had I started up the next hill than the Enfield began shaking its head and fishtailing wildly as the tyre sought in vain for traction. Cursing, pushing, feeling as though my heart were about to burst out of my chest and explode, my vision spotted with dancing black dots, I coaxed the bike up, over, and down the other side. Balancing on shaky legs, I extended the sidestand before collapsing across the tank. Trying to fill my lungs, I waited for my heart rate to decrease until I was fairly confident I wasn’t having a coronary attack. At sea level there’s an effective oxygen content of 20.9 per cent but at 4500m it’s almost halved. Any kind of exertion results in a sensation not unlike drowning on dry land.

Deep breaths

Breathing almost normally, I trudged back to lend a hand and together, gasping for air like landed fish, we pushed, pulled and nursed the remaining bikes to firmer ground. As John fought his way towards the crest of the first hill he lost his footing and toppled over, the bike trapping his ankle between the steel luggage rack and an icy rut. He screamed in agony. Carefully, we righted the bike, but he continued to lie in the snow, hands clutching his ankle, eyes squeezed tightly shut against the pain. Nervously we waited. The closest hospital was a day’s ride away. If he’d broken his ankle it would be less hassle to club him with a rock and toss him in the river than to get him to medical help.

A minute later, cursing like a sailor with Tourette’s, he hobbled to his feet and limped up the hill. We wouldn’t need to murder him and report him missing after all.

Froze over

Snow crossing number four surprised us like an unexpected kick in the cobblers.

It was only 30 metres wide, but it was short and tricky.

A shallow stream ran beneath a sloping wedge of snow that tipped into a ditch preceded by a narrow ridge of uneven rocks. Jay went first, slowly, deliberately, delicately balancing throttle and clutch as he crawled across the rocky ridge and onto the snow, where his front wheel immediately began to slide towards the ditch. Having positioned ourselves accordingly, we manhandled his bike to the other side of the slushy wedge, down over some large stones and into the wide stream running down the ‘road’. The process was pains-takingly repeated until John’s was the last bike remaining. Worried about damaging his already sore ankle, he asked me to ride it for him.

Dropping your own bike is bad enough, but dropping someone else’s is exponentially worse, and my nerves were far from soothed by the discovery that his bike tankslapped like a wet noodle in the wind.

With some welcome helping hands, I managed to coax it without incident to safer ground and, finally, we were finished.

What an ordeal. We’d spent more than three hours pushing and pulling six bikes across four snow crossings totalling just 500 metres of high-altitude Himalayan real estate. Slipping, sliding, cursing and collapsing in damp, breathless piles, we fought to suck air into our oxygen-starved lungs. It had been pure hell. Except colder. And a lot more slippery.

But we were done.

Catch cold

By 5.00pm we’d been on the road for nine hours and covered just 70km. However, Gramphu was only 18km away. It took two more hours.

Waterfalls crashed down the mountainsides flooding the dirt tracks and gravel-strewn goat paths on which we were riding.

Not far from Chhatru, we rounded a corner and were met by the sight of a truly frightening volume of water rushing across the road.

Tumbling down from on high, it spewed across the narrow track in a flood of white-water before shooting over the edge and falling a thousand feet to the valley floor.

We watched carefully as Rajesh made the first attempt, looking for where the largest rocks were hiding and plotting our routes to avoid wallowing in the deepest sections. Jay made it through next with no discernible drama, but Yogi rode barely three metres before getting hopelessly stuck. Somehow, improbably, he’d managed to perch his bike atop a rock and could move neither forward nor backwards.

Now, Yogi is a lovely fella. He’s a quiet teddy-bear of a man with an infectious grin and a proclivity for wandering around sans trousers.

So I wanted to help. I really did. But my boots were finally starting to dry and the water looked really cold. As he struggled to release his bike from the water’s chilling grip, Rigzig waded in to help.

Within seconds he was out, dancing around like a man with wasps in his undies, trying to force blood and warmth back into his freezing feet. Moments later, he ran back in to deliver a heroic Yogi-freeing shove.

A staunch proponent of the theory ‘when all else fails, give it gas’, I entered the turbulence quickly. The water barrelled into me, snatching at my front wheel and trying to shove me towards the deadly drop that beckoned from a metre away. Bouncing over a couple of submerged rocks threw me off course and before I knew it I was pointing directly at the edge. Instinctively I leaned left, cranking the bars, dabbing my feet and throttling away from the danger.

As my front wheel made dryer land I was aware of an uncomfortable creeping sensation and, with a sudden rush of clarity, understood the veracity of a fundamental motorcycling truth; the only thing worse than feeling cold water soaking into your boots is feeling it slowly trickling into your groin.

Hunt and gather

For most of the day the stunning scenery had been no more than an afterthought – a gorgeous distraction that made the hardship a little easier to bear. Glacial streams cascaded down from snow-covered peaks, misting the valleys with fluttering veils of spray. Cotton-wool wisps danced around the crowns of snaggle-toothed summits that rippled into the distance like sedimentary rock blips on the heart monitor of the world. It was spectacular.

Stunning.

But magnificent vistas aside, by late afternoon I was thoroughly sick of water crossings and cold, wet feet. It had been a staggeringly physical day; the most technical and extreme riding I’d ever done.

Bar none. Without a doubt, we would look back on this day with an incredulous shake of the head, because it had been so unremittingly, horribly, hard.

In Gramphu, we found the only hotel that still had rooms available. A quick look around left little doubt as to why. Essentially still under construction, it boasted no restaurant, no heat, and a filthy hallway stacked with building materials. Our room had no lock, the curtains were lying in the dust beneath a plastic table, and the bed was cloaked in decidedly unhygienic looking blankets. Although there was a shower head sticking out of the wall, it produced no water. And if there was one thing I’d really been looking forward to, it was chasing the chill from my bones with a very long, very hot shower.

Grumbling at the injustice of it all I pulled on dry socks and running shoes then balled up the curtains and stuffed them into my boots hoping they might soak up some of the moisture before I had to put them on again. With no spare footwear, poor Tim was forced to suffer with wet boots as we headed out into the bitter evening air in search of food.

One down

Later, back in our dingy room, we crawled fully clothed into our sleeping bags and, ignoring the scent of mould and dust, yanked the duvet over us. It had been a murderous day, but we’d survived. The bikes were still running, and even though John had given us all a good scare, there were no broken bones or significant injuries.

As I drifted off, I dared to hope that the worst was behind us. The next day we would attempt the notorious Rohtang Pass, but it couldn’t possibly be any worse than what we’d just endured.

Could it?

Comments